Let’s Talk Yeast

Since it always helps to start at the beginning, let’s first define what yeast is in the world of baking. It’s a fungi. The strain — out of some 1500 known species of the microbe — that’s best suited to baking breads and pastries. You’ve heard the Latin name before I’m sure: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, essentially “the brewer’s sugar fungus”.

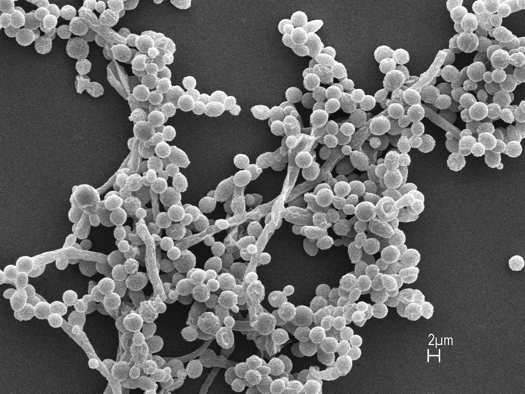

Baker’s yeasts are very, very simple organisms, single-celled little bugs that have but three jobs: to eat, to excrete and to reproduce. As they carry on in this way they’re highly effective at turning simple flour pastes into doughs full of little holes that bake up all light and fluffy-like.

So how do they achieve this miracle? Not being a microbiologist I can’t really get into the guts of how yeast metabolism works. However I can say that they can eat only the simplest of sugars: monosaccharides like glucose and fructose and disaccharides like maltose. In the process of consuming a molecule of glucose a yeast organism gathers energy for itself, and in return delivers two molecules of alcohol and two molecules of C02. I think it’s a decent bargain.

The thing about yeasts is that they can’t move of their own accord. Unlike the paramecia that we all studied in school, which have little hairs on them called cilia that help them move around, yeasts are stationary creatures. When they reproduce, they do so by budding, simply growing smaller versions of themselves on their bodies. Which don’t move either.

They grow on food, they don’t move to food, except by accident. So if they’re going to do the job we want them to do, we have to manually shift them from food supply to food supply. This is why dough kneading and stretching are so important.

Anyway there’s much more to say about yeast, but just now I have work to do, so I’ll pick this up again…probably soon.

Hi Joe,

For reasons that have nothing to do with baking, I recently stumbled on the 19th/early 20th-century technology called “aerated bread,” which used carbon dioxide instead of yeast for industrial baking – as I understand it, was intended to preserve the comparatively low quantity of protein in British-grown wheat, while still achieving something fluffy and bread-like. Have you ever heard of this? Do you know anything about what it was like?

Great idea for a post, Jen! I’ll answer this on the blog!

– Joe

I feel like I’ve made it to the big time 😉

Believe me, you haven’t. 😉

– Joe

I just put a batch of bread dough into the ‘fridge for twelve hours for a little slow-proof retardation, but it will probably have to wait until 24 hours due to my real job’s schedule change…should I give it a quick punch down and fold before I leave at 4 AM?

Hey Dave! Only if it’s extremely puffy. Otherwise the cold will pretty much keep it in stasis.

– Joe