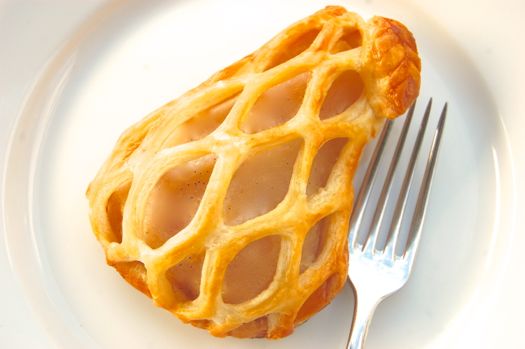

Is the vanilla slice really the chocolate chip cookie of Australia? If so, those Aussies are more sophisticated than we give them credit for. Granted most home versions are made with powdered custard and either store bought puff pastry or mildly sweet biscuits, then topped with simple powdered sugar icing. Still pretty cool though, no?

Objectively speaking, vanilla slices resemble both Napoleons and galaktoboureko, but in truth they really are their own thing. The commercial versions are, at least from what I understand, so heavily gelatin-thickened that they practically bounce, hence their nickname which I won’t repeat here for fear of getting more irate comments. While I originally thought I’d try to replicate that density, in the end I decided that just getting a custard layer this thick to stand and slice neatly was enough. But feel free to add more gelatin, those of you who prefer yours with a stouter texture.

READ ON