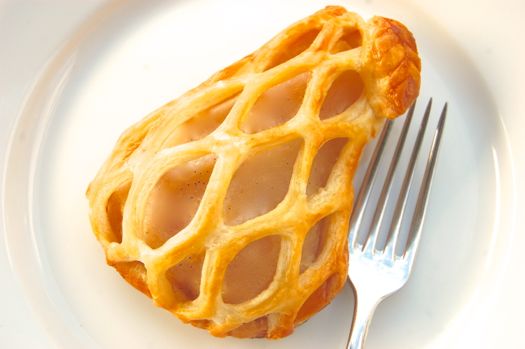

…when you’re just going to cook them in the oven anyway? A good question, reader Toni. The answer is: enzymes. Pears will turn brown when they’re baked if they aren’t poached first. That browning is a result of enzymes that activate when the flesh of the pear is cut.

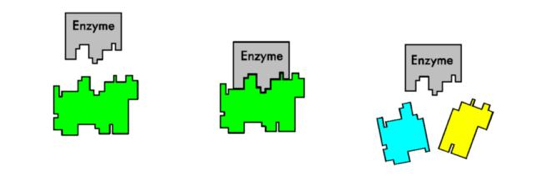

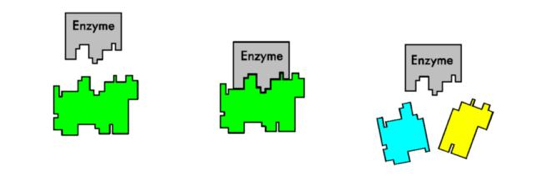

In an uncut pear these browning enzymes (polyphenoloxidase and peroxydase) are kept inside special compartments in the flesh of the pear, away from both oxygen and the compounds these enzymes commonly interact with, molecules called phenols. The trouble comes when those tiny structures are damaged by, say, cutting or bumping the fruit. At that point the enzymes are freed from their little holding cells and start to run wild. With plenty of oxygen at their disposal (which they need in order to do their job) they hop from phenol to phenol breaking each one into pieces. The resulting wreckage is a variety of smaller molecules, some of which are melanins, or brown pigments. The longer cut pear flesh is exposed to oxygen the browner it will get until all the phenols on the cut surface of the flesh have been sliced and diced, and the flesh is a mottled tan.

READ ON