The (Much Abbreviated) Life and Times of Zhuge Liang

Think of the Three Kingdoms period in China as roughly analogous to Arthurian legend in the West. Like King Arthur and his knights, the central actors in the Three Kingdoms lived in the first few centuries A.D.. In the same way Sir Thomas Mallory romanticized and popularized Arthur, Lancelot and Percival in Le Morte d’Arthur in 1485, Chinese novelist Luo Guanzhong glamorized Zhuge Liang and his contemporaries in Romance of the Three Kingdoms in the late 1300’s.

And while Romance of the Three Kingdoms is much more historically accurate than Le Morte d’Arthur (the third century Chinese kept far better records than the pre-Saxon Birts), it serves much the same purpose culturally. Over the centuries it’s spawned folk tales, books and operas. More recently it’s been the inspiration for comics, websites, video games, cartoons and full-length Lord of the Rings-style feature films. There are Three Kingdoms fan fiction books, role playing games and figurines, and heaps of miscellaneous merch. So while on the one hand it’s legitimate culture and history, on the other it’s nerd heaven.

The essential story covers a very brief period of Chinese history, 220-280 A.D., a complicated and extremely bloody few decades that followed the dissolution of the Han Dynasty. The Empire split into — you saw this one coming I bet — three kingdoms: Wei, Wu and Shu, each of which was ruled by its own self-proclaimed emperor. Wei, in the north, was in the hands of the evil Cao Pi. To the southeast there was Wu, ruled by the feckless and opportunistic Sun Quan. Shu, the redoubt of the virtuous, had the brave and well-intentioned — but strategically challenged — Liu Bei.

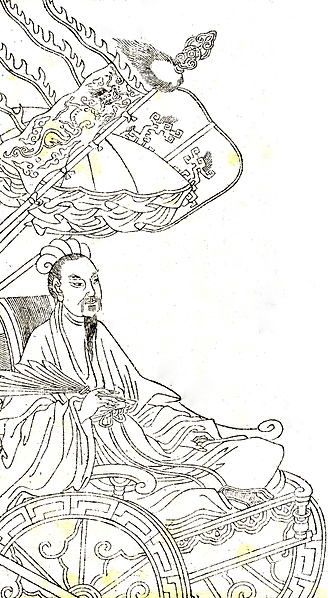

Which is where our hero Zhuge Liang enters the picture. In the run-up to the Three Kingdoms period Liang was a person of some notoriety, renown as an intellectual recluse with an ugly wife. Full of under-utilized military potential, he was known as the “crouching dragon.” In the year 208, good guy Liu Bei was on the run from the bad guys in Wei and was searching for a military brain better than his own. Told by a friend of the brilliant hermit’s talents, Bei commanded that Liang appear before him. When Liang refused, Bei was forced to visit Liang’s house and beg him to come out of seclusion and become his right hand man. After three visits, Liang finally relented.

It’s here we start to see the enduring appeal of Zhuge Liang. He’s the hero of the armchair statesman, of which I confess I am one. His example offers people like me the illusion that one day the Secretary of State will show up at our door, confess what a fool he’s been, and beg us to quit being so selfish and assume the burden of leadership. Sigh. I suppose if there’s no one else to clean up this mess…

Ulysses S. Grant is another one of those. Sure I’m a middle aged nobody now, but one of these days….just you watch! Of course like Grant, Zhuge Liang was no nobody. He was by 208 a well known scholar and inventor, and when he became Liu’s advisor, then de-facto ruler of Shu when Liu died in 220, no one was particularly surprised. Liang led his kingdom through several successful military campaigns before his untimely death from illness in 234. Along the way he wrote poetry, penned books on military strategy and invented both a precursor the wheelbarrow called the “wooden ox” and an improved version of the repeating crossbow. And let’s not forget the human head-shaped dumpling. That’s no small potatoes.

But of course like the virtuous Sir Galahad, the reality of Zhuge Liang is less important these days than the character archetype he represents: the shy, brilliant, high-minded intellectual forced by a quirk of fate into the limelight and thence to greatness. The Three Kingdoms period is long over, but there will always be a market for a Zhuge Liang.

Fascinating. I won’t even start on the ugly wife stuff (I mean, was Liang himself a dashing handsome prince?), but I do find it interesting that the number three is so magical in literature, stories, fairy tales, etc. outside of Western culture as well as within it.

After three visits, Liang finally relented.

I thrice presented him a kingly crown, Which he did thrice refuse.

Add to that three wishes, three bears, three pigs, three three three!

So of course, you will give us three different recipes for filling these Baozi, right?

But of course! And the ugly wife part has context. I left the reference hanging out there…I dunno, just because. Her name was Huang Shuo. So the story goes her father, an intellectual and peer of Liang’s named Huang Chengyan, approached Liang one day and said something to the effect of “I’ve heard you’re looking for a wife. I have an ugly daughter who is just as clever as you.” That Liang married her was taken as evidence of his exquisite wisdom and smarts, though apparently more than a few people in his village made fun of him for it!

People weren’t as sensitive then. Thanks Chana!

– Joe

Ahh… brains over beauty. I quite like that in a guy.

On one hand, Joe’s blog is both culture and history, on the other it’s nerd nirvana!

In the midst of the Internets Joe Pastry was aware of an arm clothed in white samite, that held a fair rolling pin in that hand.

By virtue of viva voce, the shy, brilliant, high-minded blogging intellectual was forced by a quirk of fate into the limelight and thence to greatness!

This just in…obscure baking geek becomes Obama’s latest recess appointment to the UN…developing…

When you assume the burdens of leadership, will you ply our adversaries with laminated pastries?

That and large amounts of filthy lucre, yes.

– Joe

It seems Lhuge Liang was a greater man than Ulysses, able to capably run the country after military exploits, instead of becoming a pawn for politicians (allowing the mildly termed Reconstruction in the South after a flawed election, partially due to Florida). I do like rice pudding too, and steamed buns which are a recent discovery.

Nice comment! Thanks Naomi!

– Joe