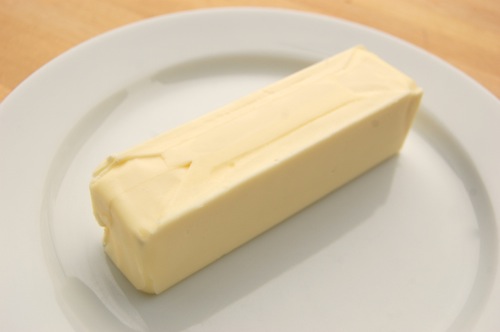

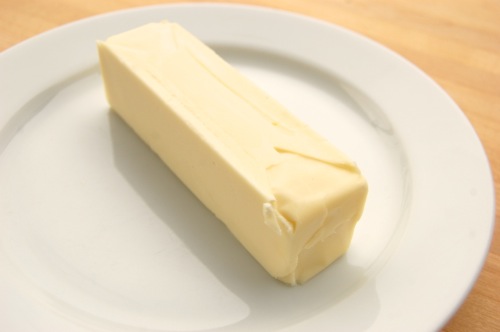

Sweet Cream Butter

Most American butters (as well as most Canadian and British butters) are “sweet cream” butters, which means that they’re made from cream that hasn’t been allowed to sour at all. This was a big selling point in the days when dairy wagons frequently showed up late to collect cream from farms, by which point the product had fermented a bit. Butter made from soured cream was acidic and cheesy and mostly unpopular with American consumers. For that reason some dairies would “correct” the cream with an alkaline (like lye) which neutralized the acid but brought even more off flavors to the party. “Sweet cream” butter was bland, but far fresher tasting.

READ ON