Strudel Moves North

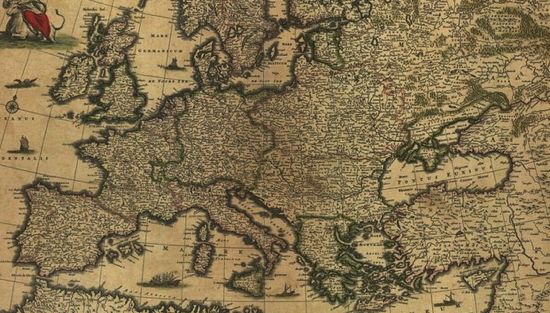

I mentioned below that Hungary remained a battlefield for decades after 1526, as Ottoman and Habsburg forces swept back and forth over the region fighting for control. The logical question is: when did it all end? When did strudel finally make the leap northward?

Those of you who’ve read the blog for a while may know that the turning of the tide for the Turks occurred in 1683, at the most baking-intensive conflict in the history of man, the Battle of Vienna. From that point onward the Ottoman Empire was either in retreat or stagnating (though it’s important to remember that it endured in some form for almost another 250 years, until just after World War I).

The Habsburgs moved into the conquered territories where they found, among other things, strudel. The dish was shortly adopted by the culture. The first recipe for strudel in German dates to 1696, just a few years prior to the end of the Ottoman-Habsburg wars. Sixty or so years later strudel was said to have appeared in the court of the one and only female ruler of the Habsburg Empire, Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina. Whew, that’s a mouthful. Maria Theresa evidently knew a good thing when she saw it, and the dish shortly became very, very popular.

All of which is not to say that strudel was an effete indulgence. Unlike most other Viennese pastry, which was high-end stuff, professionally produced and mostly enjoyed by people with money, strudel was common fare. It appeared in German language cookbooks in the 1830’s, but by that time housewives all throughout Austria and Hungary were making it. Many of them were Jewish, which is part of the reason strudel also remains a fixture of Jewish cooking to this day.

“Baking intensive” is right – various myths credit not only the croissant but the bagel and the kugelhopf to events at this siege. I’m surprised no one’s come up with one for the strudel. (“As the besieged Viennese children sought way to amuse themselves, a baker invented the flat layered strudel for them to put on their feet as they skated the frozen streets”.)

Strudel isn’t the only Austro-Hungarian specialty that found its way into Jewish baking. Someone here in LA pointed out to me that if I wanted to find samples of the kipfel, the kaisersemmel and other Viennese classics, I should go to the Fairfax district where there are numerous Jewish bakeries. Arguably, the first really good bread available in America, long before artisanal bakeries, was in Jewish neighborhoods (bread historian Steven Kaplan credits his upbringing in New York with introducing him to really good bread at a time when the standard American bread was Wonder).

Otherwise, I will always associate strudel with Mrs. Herbst’s, whose famous bakery on the Upper East Side was right near our home. I of course took it for granted and only realized decades later what a treasure we had lost when it closed.

You should write that myth yourself, Jim. It’ll be picked up by some newspaper food section writer in less than a month!

But now you’re making me hungry. There were/are great strudels in my old Chicago neighborhood, a place called Dinkel’s on Lincoln Avenue. That place is still open…long may it remain so!

– Joe