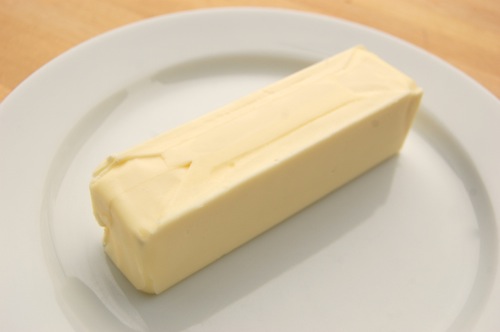

Shortening

Shortening is pure vegetable oil, hydrogenated to give it a firm texture. It’s different from margarine (another hydrogenated fat) in that it was not created to be a substitute for butter, but rather as a substitute for animal fat, specifically lard. How does it stack up? Rather well. Like lard it’s all fat with no water in it. That means it’s great for things like biscuits and pie doughs, which lose some of their crispiness and flake with butter because of the water butter contains.

Unlike lard, however, it’s completely neutral in flavor. It’s also quite a bit less expensive. It also melts at a much higher temperature, around 118 degrees Fahrenheit, which is a good thing for things like cookies and (American) biscuits, since you get a lot less spread. And did I mention it keeps indefinitely at room temperature? No wonder that the emergence of shortening in the very early 1900’s coincided with a steep drop-off in the popularity of lard.

READ ON