A post on eggs could go on almost indefinitely. However since I want to focus on the egg as ingredient, I’ll do my best to keep this short and useful. The logical place to start is: how are eggs used in the pastry kitchen? I can think of three main categories of use: as a structural component in cakes, as a thickener in custards and creams and as a foam in batters, meringues, frostings and the like. It’s a pretty crude taxonomy when you consider how much eggs offer the pastry cook in terms of flavor, enrichment and color, but it seems functional to me.

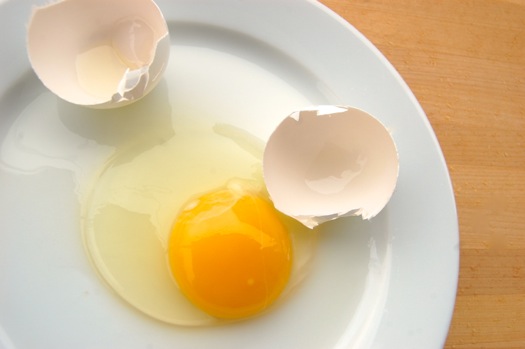

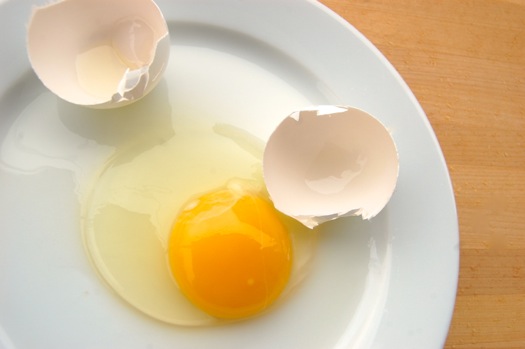

Eggs come in different colors, sizes and grades. For our purposes I’ll focus on the basic white, large (as opposed to “peewee”, “small”, “medium”, “extra large” or “jumbo” as defined by the US Department of Agriculture) chicken egg, since that’s what most pastry recipes printed in the States call for. They’re also the most commonly available egg for home bakers and commercial bakers alike. Those that use shell eggs, anyway. Large eggs weigh about two ounces. The white weighs about an ounce, the yolk about half an ounce and the shell accounts for the rest.

READ ON