Reader Dan writes:

Hi Joe. You say that George Washington Carver is “one of” your favorite food scientists. Who are some of your other favorites if I may ask? Can you give me your top ten?

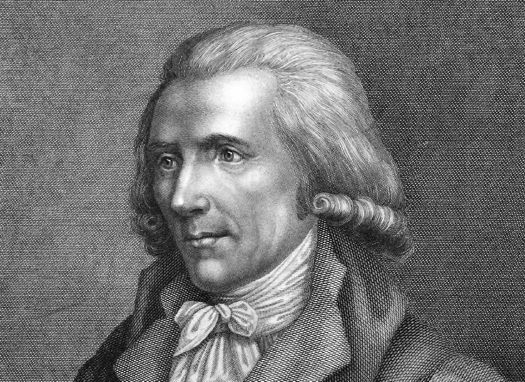

I’m not sure if Dan is on the level here or if he’s having me on. But it just so happens I do have several food science heroes, whose dreamy portraits adorn my walls. There’s Nicholas Appert, the inventor of canning, he’s really the grandfather of modern food science. Alfred Bird, inventor of stable baking powder and instant pudding (custard). There’s Otto Rohwedder, the sliced bread guy, chocolate chemist Coenraad Van Houten, good ol’ Louis Pasteur, you can’t forget him. To tell you the truth “food science” encompasses so many different

READ ON