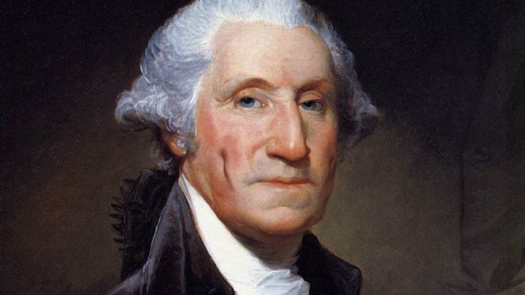

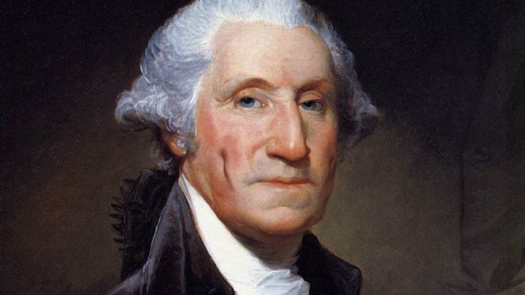

Since we’ve been talking about the American and French Revolutions the last couple of weeks, it seems as though a brief stop to recognize George Washington is in order, since his birthday is this week (February 22nd). Here in the States we sort-of celebrate Washington’s birthday on “Presidents Day”, which was yesterday, though we’re also supposed to be celebrating Lincoln’s birthday as well, and maybe other presidents, and maybe the institution of the presidency in general…no one really knows what this silly day is about, except that the mail doesn’t come.

It’s my view that Washington, mensch that he was, deserves his own celebration. He was either the greatest or the second-greatest president of the United States. It’s a toss-up between him and Lincoln. What did Washington do that was so great? Well we all know

READ ON