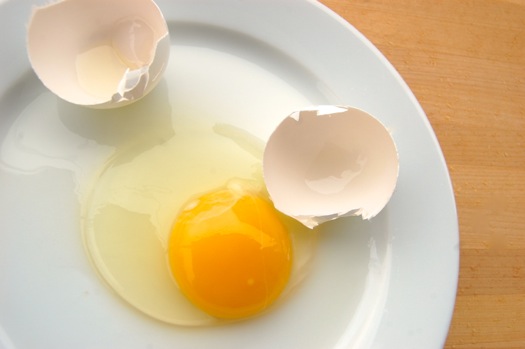

Egg Yolk

That’s a very pretty, upstanding yolk, no? It’s the mark of a fresh egg. If you’re ever in a position where you need to evaluate the relative age of an egg, a yolk is a good place to start. If it’s fairly roundish and bright yellow, and is sitting high atop a slightly milky-looking mound of almost gel-like egg white, your egg is extremely fresh. Make cake, cookies or muffins out of it. Or better still cook it up, because fresh eggs make mighty good eatin’.

Old eggs are very different in their appearance just out of the shell. The white becomes very clear and watery due to a progressive change in the pH of the egg, which begins as soon as the egg is laid. That change in pH causes the proteins in the white to drift away from each other, dispersing the large aggregations that formerly made the egg white jelly-thick and whitish. As that happens the membrane around the yolk starts to weaken. More water from the white enters the yolk, diluting its pigments and giving it a pale appearance. As that happens the yolk membrane stretches out, causing the yolk to lie almost flat. If you’ve ever tried to separate an old egg, you know just how weak that membrane is after many weeks of sitting. If the egg is sitting at room temperature, the pH change happens many times faster.

READ ON