Master of the “Mounted Piece”

The fine arts are five in number: painting, sculpture, poetry, music, and architecture — whose main branch is pastry.

God I love the arrogance of chefs. The Lighthouse at Alexandria? The Colossus of Rhodes? Child’s play compared to that centerpiece I made for the buffet the other night. I mean did you SEE that thing?? Antonin Carême was more entitled than most to that attitude. He began building pièces montées — huge table centerpieces — at the age of seventeen, and studied architecture informally on his own starting at the age of thirteen. Pretty good for an illiterate peasant who grew up in Paris amid the French Revolution. Carême’s father literally abandoned him on the street one day at the age of eleven, telling him he was too smart to live at home in poverty with his twenty four sisters and brothers. Proving his father’s point, Carême got a job that night at a tavern and shortly began teaching himself to read and write. Within a year or two he was making regular trips to the French National Library where he paged through books on travel and especially architecture. He taught himself to sketch and at the age of fifteen began working for Sylvain Bailly, the top caterer in Paris.

It was a good time to be a cook. Post-revolutionary Paris was experiencing a culinary boom. The members of the French aristocracy had either fled or lost their topknots during The Terror, which left their personal chefs unemployed. With no fancy estates to work on, these craftsmen — many of them extremely accomplished cooks and bakers — went to work for themselves. They opened cafés, pastry shops and restaurants, the best of them becoming quite famous. They catered not to “the people” but rather to Paris’ new political elite: elected representatives from all over France. Paris became a seat of power in a whole new way as politicians (and the deal-makers that followed them) them flooded into town. All needed hospitality. Grand aristocratic balls were out, but state dinners were in, and Bially was usually the man the bigwigs called.

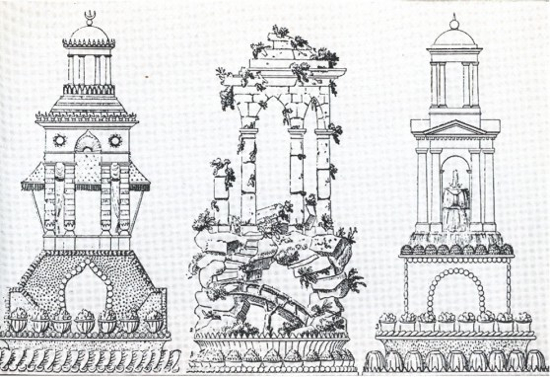

Increasingly, because those bigwigs wanted to see what Bially’s new Boy Wonder, Carême, was up to. Carême’s graceful architectural centerpieces were becoming the talk of the town. Though not as big and ostentatious as the entremets that preceded them, his pièces montées made up in detail and artistry what they lacked in size. Carême considered them his crowning achievements and over the course of his life came up with hundreds of original designs. Most were based on, no surprise, buildings: temples, pyramids and other famous structures. However others depicted natural scenes and sometimes more abstracted shapes. The new political class (and eventually the new Napoleonic aristocracy) thrilled to his sugar paste and nougat creations, quite frequently keeping and preserving them for the long term. To Carême that seemed only fitting as he considered his creations not merely imitations of architecture, but architectural works in their own right.

In that judgement he clearly went too far, though it’s true that to this day you find a fair amount of overlap between the disciplines of pastry and architecture. More than a few party chefs are former architects, and while I’ve never heard of a former pastry chef becoming an architect, there’s probably an instance of that out there somewhere. Maybe Frank Gehry. Those metal curls of his sure look like chocolate shavings to me.

If you should find yourself in France’s Loire Valley you must visit Chateau Valencay and step inside Careme’s kitchen, where he created elaborate dinners for Napoleon’s diplomats. It was thrilling to stand in the middle of his large “modern” kitchen surrounded by beautiful copper pots and pans and imagining what it would be like to be apart of the excitement working on one of his masterpieces.

p.s. the rest of the chateau and grounds are very lovely too.

I’d love to see that Linda. heck I’d just love to go to France!

My 6-year-old is dying to go, probably because she’s watched Ratatouille too many times!

– Joe