Just Call Him “Mr. President”

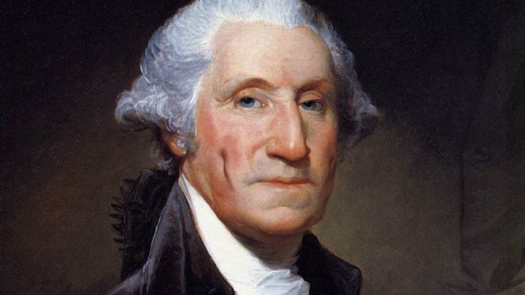

Since we’ve been talking about the American and French Revolutions the last couple of weeks, it seems as though a brief stop to recognize George Washington is in order, since his birthday is this week (February 22nd). Here in the States we sort-of celebrate Washington’s birthday on “Presidents Day”, which was yesterday, though we’re also supposed to be celebrating Lincoln’s birthday as well, and maybe other presidents, and maybe the institution of the presidency in general…no one really knows what this silly day is about, except that the mail doesn’t come.

It’s my view that Washington, mensch that he was, deserves his own celebration. He was either the greatest or the second-greatest president of the United States. It’s a toss-up between him and Lincoln. What did Washington do that was so great? Well we all know that he cut down a cherry tree, crossed the Delaware, won the Revolution, had wooden teeth, became the first president and all that. Alright maybe he didn’t cut down a tree, but he did do the other things. The point is, quite a few of our presidents served on the battlefield (Jackson, Grant, Eisenhower, Teddy Roosevelt and JKF to name a few notables) and made good in politics. Washington in truth was neither a great military mind nor an especially effective executive. His real greatness showed not so much in what he did but in what he didn’t do. Namely, become a king.

A king? In America? We don’t have those, Joe. Ah but we easily could have, and had not the right man done just the right thing when the American Revolution ended we probably would have. Why? Because autocratic military or hereditary rulers were pretty much the only kinds of rulers the world had seen up until that point. Oh sure Rome and a few city states here and there in Greece had fiddled with the concepts of democracy and self-rule a couple thousand years earlier, but by and large the idea that a nation made up of free citizens could rule itself had been discredited. When strong leaders rose and assumed power, they kept it.

Except for George Washington. In 1782 the American Revolution was almost over (yes friends, it lasted that long, 1776 was only the year we declared independence, in fact Americans had been resisting taxation without representation since 1765, which means that the American Revolution technically went on for 18 years). Oh curse me and my eternal parentheticals! Where the heck was I? Oh right, in 1782 the American Revolution was almost over and George Washington was by far the most powerful, popular and respected man in America. Congress wasn’t terribly well regarded, especially by the military which was under-fed and underpaid.

Conditions were ripe for a coup d’état, a fact not lost on a fellow named Lewis Nicola, a Colonel of the Continental Army, who wrote to Washington in May of 1782 while the army was encamped in Newburgh, New York. Nicola informed Washington that he would have the backing of the military should he decide to step into the role of king. This was the infamous “Newburgh Letter” which, had it been sent to any man other than Washington, could easily have changed the course of American history. Happily for us and for lovers of democracy everywhere, Washington was appalled. He blasted Nicola’s suggestion in a letter dated the very same day (showing he didn’t even sleep on it). The following year in 1783, after the close of the Revolution and the signing of the Treaty of Paris, Washington resigned as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Armies and went home to Mount Vernon.

To say that this act stunned the world is putting it mildly. Even Washington’s old foe, King George III of Great Britain, called Washington “the greatest man of the age” when he heard the news. There was simply no precedent for this behavior. As I mentioned above, people who held the sort of power Washington held had always kept it or at the very least passed it on to their children, siblings or extended family. Washington didn’t even name a successor. He simply walked away, setting an example that American presidents have followed ever since. Talk about leadership.

Later, as if to underscore the point, Washington did it again, for as we all know he was elected as the first president of the United States in 1789. No one knew then exactly what an American President was or was supposed to be like. Washington invented the role, again setting an example we follow to this day. He eschewed honorifics like “Your Excellency”, “Your Majesty” and “Your Highness” in favor of a simple “Mr. President”, and established the codes of dress, manners and customs we associate with the office. And then after two terms, the second of which he didn’t even want, he resigned and went home, again to the shock and amazement of the world.

Today it’s said, always sarcastically, that the greatest thing this-or-that politician, bureaucrat, coach or business leader ever did was resign. Where Washington is concerned that’s absolutely true, funny as it sounds. But it’s more than any man of any real power before him ever managed to do, and that’s what made his resignations historic, monumental really. Without Washington’s wisdom and integrity, America and indeed modern democracy itself wouldn’t be the same.

I’ve always admired Washington. He could have been emperor for life if he wanted it, but no. It takes a special man to walk away from the offer of unlimited power.

It really does. Talk about a contribution to humanity — he made it. He may have been something of a mediocrity in other areas of his life (though not in height of course, the dude was huge) but when it came to bravery, character and conviction he had no equal. A lot of us like to think we’d do the same thing in his position. Hardly any of us would though, especially had we lived in his day and age when no one willingly laid down power, ever. I said it before: what a mensch!

Thanks as always, Ellen!

– Joe

I alway thought John Adams didn’t get as much credit for the same thing, with critical differences.

Washington went out the most popular man in America, and could’ve easily stayed on as a permanent (if symbolic) sovereign after his term ended. He also had a successor (Adams) coming in with many similar views, so he knew there would be continuity of government and policy.

Four years later, Adams was *literally* the least popular president in history. He dealt (sometimes poorly) with dozens of major issues that Washington never had to or never chose to address, and lost an incredibly close and confusing election to Jefferson in 1800. This was the first true handover of power between one administration to another, and it could’ve gone very wrong.

While Adams had been commander-in-chief, and had passed strict (unconstitutional) laws against speech and political action, he lost the popular vote by a landslide, and could easily have started a civil war and ended the Union if he contested the election.

The fact that he left office willingly (if not happily) set a significant precedent for the US and reinforced the legal authority of the Constitution. It also brought up flaws in the electoral process regarding running mates, rectified in the Twelfth Amendment a few years later.

Great comment. I don’t know very much about Adams, though I do recall how the Alien & Sedition Acts made him something of a pariah. Then again, the French Revolution was starting to spill over onto our shores…anarchy threatened…what’s a poor man to do? It doesn’t seem like he should be making such regular appearances on “worst presidents” lists. Or so says I, anyway. Thanks, Fluffy!

– Joe