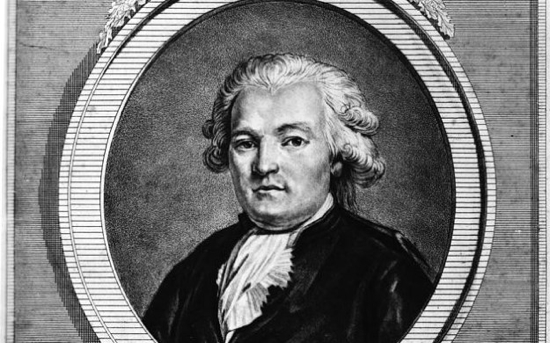

Jean Brillat-Savarin

Everyone who knew Jean Brillat-Savarin knew he was an epicure. No one, however, had the slightest inkling that he was the burgeoning author of a ground-breaking book on gastronomy. Anyway not until just before he died, in 1826. For Brillat-Savarin worked on it in secret, spending some 25 years creating the semi-scientific, semi-philosophical, semi-humorous 8-volume opus that would become known as The Physiology of Taste, or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy. The book came out late in 1825, and then anonymously. Still, by February of ’26 Brillat-Savarin was dead, having caught pneumonia at a memorial mass for King Louis XVI at St. Denis Cathedral in Paris. As word of his achievement spread among his friends and acquaintances — very probably at his funeral — the result was mild shock.

Brillat-Savarin wasn’t a philosopher, not a scientist nor a chef. Rather he was a sober and respected lawyer and judge from the city of Belley in eastern France. Sure he liked to eat. His father was a noted gourmet, as were his two brothers. But this? His other two books — one on macro economics and another on the history and legal implications of dueling — were snoozers. Without doubt, more than a few of his associates walked away from his memorial thinking I should have spent more time talking to Jean.

It’s not that Brillat-Savarin didn’t have an interesting life. Already an accomplished attorney when the French Revolution Broke out in 1789, he was in favor of the Revolution, but not of its consequence, the Terror, in which the emboldened Jacobins instigated a bloody off-with-their-heads purge of both the aristocracy and the more moderate of the revolutionaries, the so-called Girondists. Brillat-Savarin was one of these, as were his fellow townspeople. No, the people of Belley didn’t like the monarchy. However they didn’t much like the idea of radical revolutionary rule, either. They elected Brillat-Savarin their mayor in 1792, and he did his level best to protect the citizenry from the depredations of the Jacobins. In return for his trouble he was labeled a counter-revolutionary and threatened with beheading himself. He was thus forced to flee France in 1793.

He fled to Switzerland, then the Netherlands and Finally to America. Over the next few years, Brillat-Savarin drifted from city to city teaching French and playing his Stradivarius violin to make ends meet. He lived in Boston, New York (where for a time he was concertmaster of the John Street Theater orchestra), Hartford and Philadelphia. Along the way he learned a great deal about American culture and food, and was taught to truss a turkey by no less a person than Thomas Jefferson.

By 1796 things in France had cooled down. The excesses of the Jacobins had finally brought about their downfall. Robespierre had been arrested and beheaded, the party discredited and scattered. Brillat-Savarin could at last return home to Belley where his confiscated house and property were returned to him. In 1798 he was appointed to the high criminal court in Versailles and in 1800 to the Supreme Court of Appeals, a post he held for the rest of his life.

To say he enjoyed life in Paris (where he lived ten months of the year) is putting it mildly. A bachelor pillar of French society, he was invited to all the best parties, where he met the best people, ate the best foods and drank the best wines. Surely he also there developed his many gastronomic theories and now-famous aphorisms (“Tell me what you eat and I’ll tell you what you are”). For all that he never breathed a word about the self-financed project that would come to define him for future generations of food lovers food writers. Either he didn’t want to undermine his image as an upright justice or he was just plain modest. On that point his surviving friends and relations were left to speculate.

Thanks Joe! I had heard of him but never heard of his writing. I wonder if it is available in English anywhere?

Oh my yes it is. You can even read it for free on google books if you want!

– Joe

Hmmm, can’t find it free, but it is available for purchase.

Maybe I’m not looking in the right place?

Try google books. I think you can at least read it for free.

– Joe

Loved this, thank you! I never knew much about him aside from the “tell me what you eat and I’ll tell you who you are” quote.

“They elected Brillat-Savarin their mayor in 1792, and he did his level best to protect the citizenry from the depredations of the Jacobins. In return for his trouble he was labeled a counter-revolutionary and threatened with beheading himself. He was thus forced to flee France in 1783.”

Should it read flee in 1793 ?

Quite right, Mike. Thank you.

– Joe