Rising, Fast and Slow

Reader Anna wrote in late last week to ask why big heat (i.e. around 500 degrees Fahrenheit) helps shortbread-type cakes like scones and American biscuits rise higher. Anna, you’ve made me a very happy blogger this Monday morning. Leavening is a fascinating, fascinating subject.

Baking powder doesn’t look much like an explosive, but that’s how I think of it: a cocktail of chemicals that creates a high volume of outward-rushing gas — literally “blowing up” a mass of batter or dough. Add a little water and a little heat and kablooie, you get volume.

The sad part is that baked things don’t achieve anything like the volume they could achieve, at least in theory. For batters and doughs are imperfect vessels. They leak a lot in the oven. Even choux batter leaks, despite the fact that it increases in volume by about 400% as it bakes. It’s not bad, but still well short of the 160,000% increase in volume you get when water converts into steam. That choux batter can rise even four times is a testament to the gummy, elastic network of gluten and gelatinized starch you get when you pre-cook a flour paste.

Scone or biscuit dough is nowhere near as well endowed. It’s a loose, dry-ish paste chock full of butter. Which means the gluten it contains is largely undeveloped. Coated with fat as most of those protein molecules are, they can’t attach to one another to form the stretchy gas-trapping networks they normally would, poor little things.

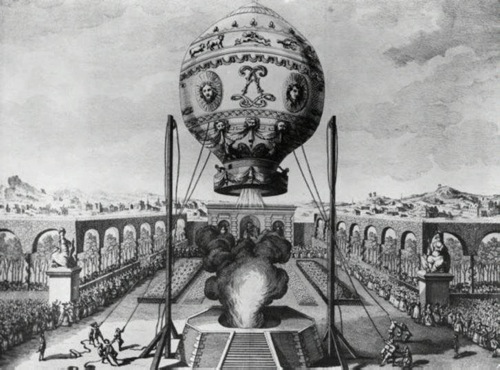

Thus instead of an efficient gas-trapping hot air balloon-like device we have a structure that more closely resembles a hot air balloon full of holes the size of dinner plates, gushing steam and gasses in all directions. Inflating it requires less a steady stream of leavening than an explosion. Which is where the chemical leavening and the high heat come in.

As you may recall from other discussions of baking powder, it has two actions (it’s “double-acting”, remember?) one when it gets wet and another when it gets hot. The faster you can get heat to penetrate the scone or the biscuit, the higher the volume of gas and steam you’ll release all at once. Thus the high oven. Pop the little cakes in and FOOM, off goes the baking powder and up go the scones. In this way we see that scones or biscuits are less like one of these than it is one of these.

Sure, they’ll still rise at lower heat, just not as much. And some people prefer a denser scone with a more refined appearance than you often get from, well, an explosion. But where American biscuits are concerned, lightness is a characteristic valued above all others. So I say…ka-boom.

i recently started baking when i received my amazing kitchenaid stand mixer for christmas and am fascinated with this “leavening” stuff! after reading this post, i did what any curious person does and hit up google. i found this awesome write-up that had pictures of all the different results. thought I’d share –> http://www.orbitals.com/self/leaven/index.html

I’ve seen that, Kat. It’s a fun piece. Thanks for reminding me of it!

– Joe

I’ve noticed that in a lot of English recipes, they suggest placing the baking tray in the oven to heat up during preheating. Apparently this extra heat also helps to “boost” the scones for a better rise.

Absolutely, Bina! Thanks for the comment!

– Joe