It All Started With Polyester

The inspiration for the Pop Tart wasn’t a recipe, it was a packaging material. A product called BoPET (Biaxially-oriented polyethylene terephthalate) otherwise known as Mylar. It’s a stretched polyester film that we mostly take for granted now, but in the 1950’s was considered a miracle product. Then, consumer goods makers had precious few choices when it came to containers or wrappers to put their…well… “stuff” in. You had cans, you had boxes, drums, cartons and crates, but that was pretty much it. And all of them had their limitations when it came to durability or resistance to environmental conditions like heat, cold and moisture. And if you wanted consumers to be able to actually see your product in the package, forget it (unless you could stuff whatever it was into a glass bottle).

Yes, there were some plastics on the market at the time. Polystyrene, nylon and synthetic rubber had all been developed by that point, but they had limitations as well. Most plastics of the time were rigid and prone to cracking or tearing, or they were easily damaged by acids, alkalines, fats, oils, solvents, what-have-you.

Mylar was different. It was not only tough it was heat, moisture and (mostly) chemical resistant. Rolled thin it was extremely flexible. It could be wrapped around folded shirts and bed sheets for shipping or fashioned into bags which could be used as box liners. This was a godsend to cake mix makers who until then had terrible problems with fats and oils weeping into cardboard boxes and staining the packages.

Mylar could also be customized in a variety of ways. Yes you could color it and print on it, but more important even than that, you could “metallize” it, which is to say expose a film of it to a vapor of aluminum or even gold atoms (you see this stuff all the time in the space program). What did that do to it? Well, in addition to all the other properties of standard Mylar, metallization plugs up microscopic holes in the plastic, reducing gas permeability to practically zero. Dry goods enclosed in it wouldn’t pick up any foul odors, and more importantly wouldn’t lose their flavors and/or aromas through long-term exposure to oxygen or by evaporation of their essential oils. These days metallized mylar — also known as “printin” — is most commonly used as coffee “foil” packaging.

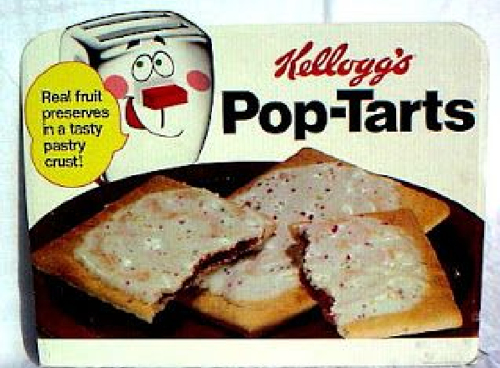

In the early 1960’s they hadn’t thought of that yet, though. But Post Cereals was intrigued with metallized mylar: what can we do with this cool stuff? First shot out of the box: dog food. Their semi-moist dog food hadn’t been taken to market yet due to spoilage concerns. But, seal it airtight in a metallized mylar bag and presto: Gainsburgers were born. Next up: Tang. Up until then Post hadn’t figured out a lid solution that would keep the delicate citrus flavors fresh. Another winner! Let’s see, let’s see…ready made baked goods. Those have never kept well on shelves before. What about those toaster-heated jam tarts we’ve been working on? Great idea! Somebody call the media!

Which is where the trouble began. More on that in the next post

We used mylar in architecture school for drafting projects. It was nice and durable (unlike cotton rag vellum), but difficult to correct. (Also, very expensive for cash-strapped students like myself.) The professors who required it were very old-school, bemoaning the CAD takeover. I had no idea it was the same thing that packaged my potato chips!

And where would all those fancy balloons be without Mylar?

Indeed! Thanks, Vanessa!